Constructing Belonging: A selection of works by J.H. Pierneef, 1901-1948: Considering Identity and Landscape as jointly constructed through formal and ideological means

-

-

This exhibition brings together a focused selection of works by J.H. Pierneef (1886–1957), one of South Africa's most influential and contested modernists. Spanning five decades of artistic production, the collection explores how Pierneef constructed a vision of South Africa's landscape shaped by aesthetic order, ideological nostalgia, and formal innovation.

From youthful studies in charcoal to luminous, late-career oils, these works map Pierneef's evolving response to land and belonging. At the centre lies a tension – between nature and architecture, individual vision and cultural myth, observation and invention. This exhibition proposes that Pierneef's work not only idealised a particular image of South African landscape, but also actively participated in constructing a visual language of identity, order, and possession.

In the context of contemporary debates around land, heritage, and historical memory, Pierneef's images continue to demand engagement – not as fixed icons of Afrikaner nationalism, but as complex artefacts of modernism, shaped by and shaping the ideologies of their time.

-

-

A Landscape Made to Measure: Pierneef’s Modernist Imaginary

J.H. Pierneef’s landscapes are instantly recognisable: rhythmic, ordered, stripped of human presence yet loaded with human design. Through disciplined line, measured composition, and stylised light, Pierneef did not so much record the South African landscape as remake it in his image — or, more precisely, in the image of a cultural ideal.

The works gathered in Constructing Belonging trace the aesthetic and ideological arc of Pierneef’s career. From the precocious charcoal rendering of House in Rustenburg (1901), created during the Anglo-Boer War, to the glowing abstraction of River Scene (1948), they reflect a lifelong quest to distil nature into harmony, permanence, and control. Nowhere is this clearer than in Die Wynkelder (c.1928), where Cape Dutch architecture rises like a monument to cultural identity, its gable a surrogate for a national style.

Pierneef’s landscapes emerged during a time of political consolidation and cultural self-definition. The trauma of the Boer War, the rise of Afrikaner nationalism, and the looming policies of racial segregation all formed the backdrop to his formal refinements. His works exclude people, but they are not depopulated — rather, they are inscribed with values. The lone farmhouse, the sacred mountain, the symmetrical forest clearing: each is a cipher for belonging, control, and aestheticised possession.

But Pierneef was more than an ideologue. His later works, particularly the softly radiant River Scene and the evocative linocut cover for Kinder-verse van Totius, show an artist capable of tonal subtlety and emotional quietude. These pieces suggest not just mastery of technique but a kind of interiority, a private response to land as sanctuary, symbol, and self.

Today, as South Africa continues to grapple with questions of land restitution, cultural memory, and decolonisation, Pierneef’s work invites renewed scrutiny. This exhibition does not seek to canonise nor to cancel. Rather, it holds these works up to the light — not to pass judgment, but to better understand the contours of a national imagination. Pierneef gave South Africa one of its most enduring visual myths. It is up to us to read it anew.

-

-

J.H. Pierneef

1886-1957

Die Wynkelder, c.1928

Oil on canvas

214 x 198 x 6 cm (including frame)

84 ¼ x 77 15/16 x 2 ⅜ in

Artwork: 174 x 158 cm

68 ½ x 62 3/16 inProvenance

Private collection, Cape Town.

5th Avenue Auctioneers, Johannesburg, South African & International Paintings, Persian Rugs & Collectibles, 27 October 2019, Lot 185.

Private collection, Cape Town.

Strauss & Co., Cape Town, Important South African Art & Furniture, Decorative Arts and Jewellery, 21 October 2013, Lot 681.

On loan to The Alphen Hotel, Cape Town, from 2001 to 2013.

A gift from the artist to Louis van Bergen, a close friend of Pierneef and proprietor of the Constantia Bottle Store in Pretoria, where the painting was prominently displayed for many years. It later passed by inheritance to the store’s subsequent owner, who consigned it to Volks Art Auctions, Pretoria, on 14 September 1994 (lot 63), where it was illustrated in colour as the frontispiece to the catalogue.

-

Painted in the late 1920s, Die Wynkelder is a major work from a formative moment in J.H. Pierneef’s development as an artist. The atypically monumental scale and commanding presence of this composition underscore the importance of the subject matter: a Cape Dutch wine cellar nestled beneath a cathedral-like canopy of trees. Dappled light and deep shadows theatrically illuminate the ornate gable, a hallmark of Cape Dutch architecture, and a motif Pierneef returned to frequently as a symbol of order, heritage, and permanence.

The 1920s were a pivotal decade for Pierneef, marked by artistic experimentation and philosophical realignment. In 1925, he travelled to Europe where he met influential figures such as Anton Hendriks, later Director of the Johannesburg Art Gallery, and the Dutch art theorist Willem van Konijnenburg. Konijnenburg’s ideas on visual harmony, proportion, and structure would leave a lasting imprint on Pierneef’s thinking. He began to move away from the impressionistic tendencies of his early career, turning instead to a more distilled, geometric style that emphasised balance, rhythm, and the underlying architecture of both nature and the built environment.

Die Wynkelder occupies a unique position in this transition. It retains a degree of atmospheric spontaneity, evident in the expressive brushwork of the foliage and ground, while also demonstrating a new preoccupation with symmetry, order, and simplified form. The strong vertical and horizontal axes, the measured repetition of windows and trees, and the formal centrality of the gable reflect Pierneef’s efforts to articulate a modern South African visual language grounded in classical ideals.

Architecturally, the Cape Dutch gable depicted here is more than decorative flourish – it is a cultural symbol. Originating in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Cape Dutch style synthesised European Baroque influences with local materials and climate-responsive design. These structures became powerful visual emblems of settler permanence in the Cape colony. For Pierneef and many of his Afrikaner contemporaries in the early 20th century, such architecture held nostalgic and nationalist associations. In a period of rising Afrikaner identity, particularly following the trauma of the Anglo-Boer War and the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, these buildings came to symbolise a rooted, pastoral ideal.

Globally, the late 1920s were a time of political and economic uncertainty. In South Africa, tensions around land, race, and identity continued to intensify, laying the groundwork for the later policies of apartheid. Pierneef’s work, though apolitical in appearance, has often been read as encoding a quiet assertion of Afrikaner cultural pride through its highly selective and ordered vision of the land.

In 1929, shortly after this painting was completed, Pierneef received the prestigious commission to produce 32 large-scale panels for the newly constructed Johannesburg Railway Station. The compositional clarity, symbolic resonance, and architectural emphasis seen in Die Wynkelder strongly anticipate the style and thematic direction of those murals. Indeed, given its scale and ambition, this painting may be understood as a proto-study for that celebrated commission.

Die Wynkelder thus serves as a key link between the artist’s earlier atmospheric landscapes and the formal, ideologically inflected style that would come to define his mature oeuvre. It is a significant and historically rich example of Pierneef’s contribution to South African visual culture – an image of place that is as much constructed as it is observed. -

-

J.H. Pierneef

1886-1957

Farmhouse, Rustenburg, 1945

Signed and dated (bottom left)

Oil on board

47.5 x 57.5 x 5 cm (including frame)

18 11/16 x 22 ⅝ x 2 in

Artwork: 34.5 x 44.5 cm

13 9/16 x 17 ½ inProvenance

Private collection, Cape Town.Literature

c.f. House in Rustenburg (Nilant 42) and House in Rustenburg (Nilant 43) in Nilant, F.G. (1986). Jacob Hendrik Pierneef (1886-1957) as Printmaker. Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery. Illustrated pp.43-44. -

This luminous landscape captures a farmhouse in Rustenburg with the stylistic precision and formal elegance that characterise the artist’s most accomplished period. Painted in 1945, during the mature phase of his career, the work distills Pierneef’s vision of the South African interior as a place of quiet order, structure, and clarity.

Set against the dramatic rise of the Magaliesberg mountains, the whitewashed geometry of the farmhouse is crisply delineated, its facade gleaming beneath a cloudless winter sky. The yellowed grasses in the foreground and the sparse vegetation, including Pierneef’s iconic stylisation of the acacia tree, signal the arid Highveld climate while contributing to the work’s rhythmic composition. Here, Pierneef’s economy of line and restrained palette evoke a landscape both idealised and specific, imbued with nostalgia for a rural order unmarred by industrialisation or political tumult.

Rustenburg was a site Pierneef returned to repeatedly throughout his life. Its topography offered him the kind of structured natural forms he sought as a painter – mountains, plains, and isolated architecture – all susceptible to the graphic simplification that defined his approach. As with his most enduring images, Farmhouse, Rustenburg merges environmental fidelity with a subtle abstraction that lifts the scene beyond documentary observation into the realm of visual ideal.

Works from this period remain among Pierneef’s most collected and studied, offering not only aesthetic value but historical insight into the visual culture of Afrikaner modernism and the ideological function of landscape in 20th-century South African art. -

-

J.H. Pierneef

1886-1957

River scene, 1948

signed and dated

oil on canvas laid down on board

70.5 x 78.5 cm (including frame)

40 x 50 cm (excluding frame)Provenance

Private collection, Cape Town. -

This rare and ethereal landscape reveals the artist at his most atmospheric and lyrical. Painted in 1948, during the mature phase of his career, River Scene departs from the structured monumentality of his more iconic vistas in favour of a softly diffused palette and an almost dreamlike evocation of light. The scene, defined by pastel washes of pale blue, mauve, and verdant green, emerges not as a topographical study but as a poetic meditation on serenity and reflection.

The composition centres on a glade of trees gently mirrored in the still river water, their foliage rendered with delicate, rhythmic brushwork. A cumulus cloud floats high in the sky, echoing the upward lift of the vegetation and enhancing the painting’s sense of vertical calm. While Pierneef’s early training in architectural draftsmanship is evident in the underlying structure, this work is suffused with a rare softness, evoking a sense of quietude that feels both timeless and intimate.

Painted a decade before the artist’s death, River Scene captures a lesser-known dimension of Pierneef’s practice: the ability to distil nature into tonal harmony and contemplative quiet. This is not the dramatic, nationalistic Pierneef of the public mural or Transvaal mountain – but rather a private and luminous vision, suggesting the universality of nature’s restorative grace. -

-

J.H. Pierneef

1886-1957

House in Rustenburg, 1901

Signed and dated (bottom left)

Charcoal on paper

78.5 x 98.5 x 5.5 cm (including frame)

30 15/16 x 38 ¾ x 2 3/16 in

Artwork: 53 x 75 cm

20 ⅞ x 29 ½ inProvenance

Private collection, Cape Town.Literature

c.f. House in Rustenburg (Nilant 42) and House in Rustenburg (Nilant 43) in Nilant, F.G. (1986). Jacob Hendrik Pierneef (1886-1957) as Printmaker. Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery. Illustrated pp.43-44. -

This early charcoal drawing, dated 1901, offers a rare glimpse into the young artist’s developing eye and his early sensitivity to architectural and arboreal forms. Created when Pierneef was just fifteen years old, House in Rustenburg predates his formal training at the Staats Art School and his influential sojourns in Europe, yet already reveals the aesthetic concerns that would define his mature practice.

Rendered in soft graphite and charcoal, the work captures a gabled homestead nestled along a tree-lined path, its Cape Dutch architecture framed by tall cypresses and bare winter branches. The carefully modulated tones and sharp vertical emphases anticipate Pierneef’s later concern with compositional structure and design clarity. Though more naturalistic than his stylised later landscapes, the drawing already demonstrates a quiet orderliness and a contemplative sense of place.

The date is significant: 1901 was the midpoint of the Anglo-Boer War, and Pierneef, of Dutch descent and part of Pretoria’s cultural elite, would have been profoundly shaped by the turbulence of this period. While the drawing does not directly reference the conflict, its calm domesticity may be read as a personal or cultural counterpoint to national instability. In retrospect, this drawing stands as a foundational expression of Pierneef’s lifelong fascination with the landscape and built environments of the South African interior, filtered through a uniquely modernist lens of balance, control, and light. -

-

J.H. Pierneef

1886-1957

Portret van 'n Voortrekker (Nilant 136), 1917

Signed and dated (top right)

Linocut on paper

70 x 63 x 3.5 cm (including frame)

27 9/16 x 24 13/16 x 1 ⅜ in

Image size: 27 x 20 cm

10 ⅝ x 7 ⅞ in

Edition unknownProvenance

Private collection, Cape Town.Literature

Grosskopf, J.F.W. (1945). Hendrik Pierneef: Die Man en Sy Werk. Pretoria: JL van Schaik, Bpk, another impression from the edition illustrated in black and white, unpaginated, Cat. No. 27.Nilant, F.E.G. (1974). Pierneef Linosneë. Cape Town: A. A. Balkema, another impression from the edition illustrated in black and white p.171.Nel, P.G. (ed.) (1990). JH Pierneef, His Life and His Work. Cape Town and Johannesburg: Perskor, another impression illustrated p.182.

De Kamper, G. and De Klerk, C. (2014) JH Pierneef in Print. Bela-Bela: Dream Africa, another impression from the edition illustrated in black and white p.191. -

One of the most graphically compelling images in Pierneef’s early oeuvre, Portret van 'n Voortrekker exemplifies his ability to synthesise portraiture with the bold formal language of linocut printmaking. Rendered in stark contrast on brown paper, the figure is monumentalised through strong contours and a sharply modelled beard, hat and jacket, conjuring an archetype of Afrikaner masculinity and pioneering resolve.

Originally created as the jacket design for Trekkerswee, a 1915 collection of elegiac poems by J.D. du Toit (Totius), this portrait forms part of a broader collaboration between two towering figures in early Afrikaner cultural nationalism. While Totius gave poetic voice to the memory of the Great Trek and its spiritual sacrifices, Pierneef offered a visual language rooted in clarity, strength, and symbolic gravitas.

The work is formally indebted to German Expressionism and Jugendstil design, both of which influenced Pierneef during his time in Europe. The blocky simplicity and high contrast reflect his mastery of linocut as both a medium of popular accessibility and ideological symbolism. The stylised “JP” monogram at upper left recalls similar treatments by contemporaries such as Henk Pierneef’s teacher Frans Oerder and the Dutch graphic artist Jan Toorop.

Today, Portret van 'n Voortrekker offers more than a cultural relic. It reveals the visual strategies by which early 20th-century Afrikaner identity was being codified — not through realism, but through a symbolic flattening that aligns the subject with the timeless, heroic, and ancestral. As with much of Pierneef’s work from this period, the image is as revealing for what it projects as for what it omits. -

-

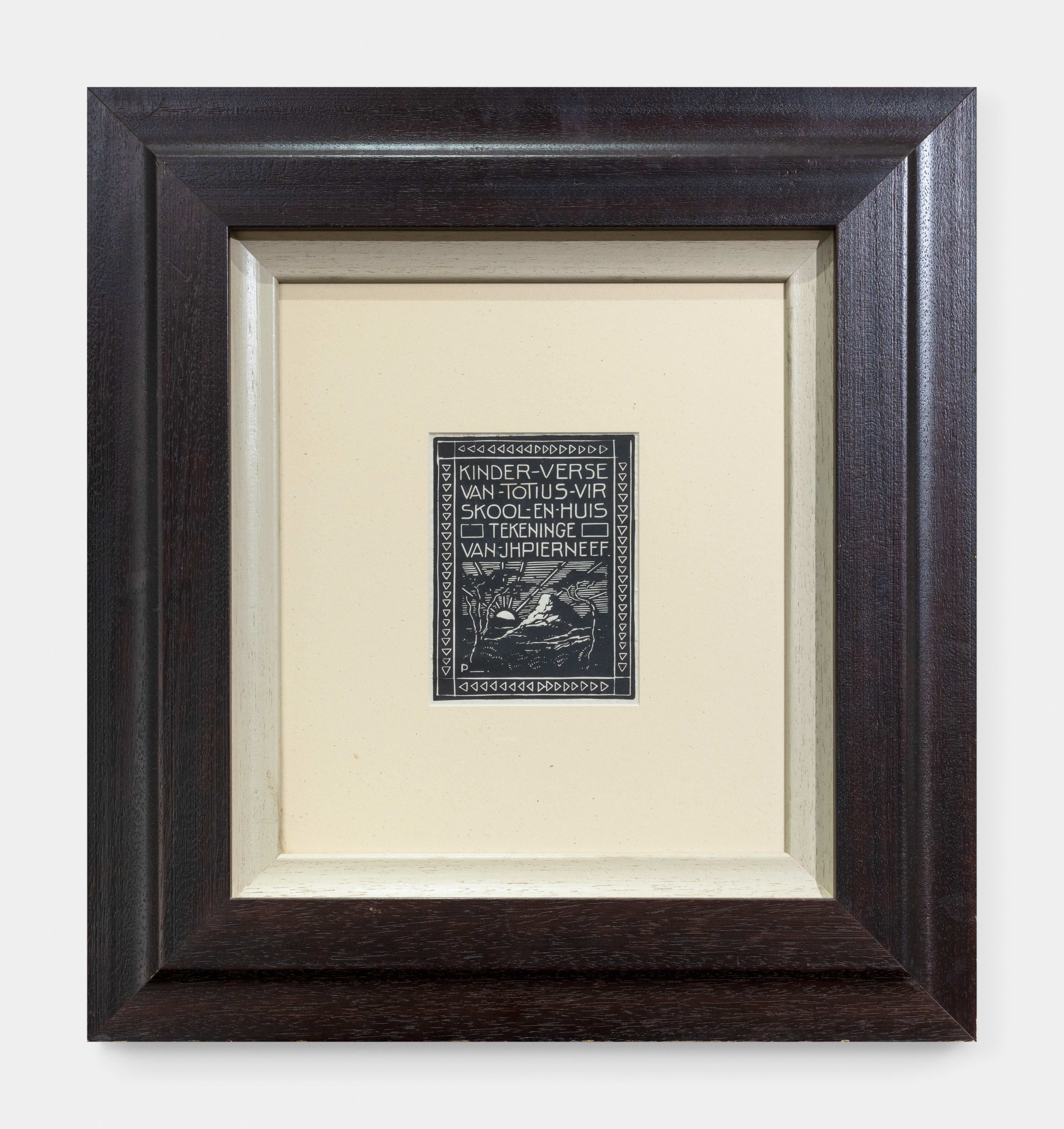

J.H. Pierneef

1886-1957

Kinder Verse Van Totuis Vir Skool en Huis

Signed with an initial in the plate (bottom right)

Linocut on paper

59.5 x 56 x 3.5 cm (including frame)

23 7/16 x 22 1/16 x 1 ⅜ in

Image size: 17 x 13 cm

6 11/16 x 5 ⅛ in

Edition unknownProvenance

Private collection, Cape Town. -

A rare early linocut, Kinder Verse van Totius vir Skool en Huis was produced as the cover design for the 1920 children’s poetry book of the same name – a popular Afrikaans-language volume by theologian and poet J.D. du Toit (Totius). Created in the formative years of Pierneef’s printmaking practice, this strikingly graphic work distills many of the formal and ideological concerns that would define the artist’s mature oeuvre: the monumentalised landscape, rhythmic patterning, and a deep affinity with Afrikaner cultural identity.

Carved with precision and economy, the linocut depicts a stylised South African koppie at sunrise, framed by thorn trees and rendered in flattened tonal contrasts. Radiating lines of light stretch from the horizon, evoking both visual drama and spiritual awakening — themes consonant with the book’s didactic Christian nationalism. The decorative border of alternating triangle motifs lends the work a frieze-like authority, transforming it into both image and emblem.

While modest in scale, the linocut offers key insights into Pierneef’s evolving iconography and design sensibility, particularly his early interest in woodcut and linocut as vehicles for mass reproduction and cultural dissemination. It also reveals the artist’s longstanding collaborations with Afrikaans-language publishers and writers — partnerships that contributed significantly to the mythologising of landscape within Afrikaner nationalism in the early twentieth century.

Examples of this linocut are held in South African institutional collections, including the Johannesburg Art Gallery and the Pierneef Museum, though the edition size remains undocumented. Works of this nature – book designs, ex-libris prints, and ephemera – are increasingly recognised for their role in shaping Pierneef’s broader aesthetic project and their significance within South African visual culture.